An international team of researchers from the Max Born Institute in Berlin, University College London and ELI-ALPS in Szeged, Hungary, has demonstrated attosecond-pump attosecond-probe spectroscopy to study non-linear multi-photon ionization of atoms. The obtained results provide insights into one of the most fundamental processes in non-linear optics. The detailed experimental and theoretical results have been published in Optica.

Femtosecond (1 femtosecond = 10-15 seconds) pump-probe spectroscopy has revolutionized the understanding of extremely fast processes. For instance, the dissociation of a molecule can be initiated by a femtosecond laser pump pulse, and can then be observed in real time using a time-delayed femtosecond probe pulse. The probe pulse interrogates the evolving state of the molecule at different time delays, making it possible to record a movie of the molecular dissociation. This powerful technique was awarded with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1999.

Some processes in nature, however, are even faster and take place on attosecond timescales (1 attosecond = 10-18 seconds). It would therefore be ideal to initiate an ultrafast process using an attosecond pump pulse, and to interrogate the system under investigation using an attosecond probe pulse. So far, attosecond-pump attosecond-probe spectroscopy has been demonstrated for relatively simple processes involving the absorption of two photons. However, since all-attosecond pump-probe spectroscopy is very challenging, most experiments in attosecond science use only one attosecond (pump or probe) pulse in combination with one femtosecond pulse.

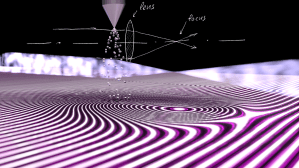

The researchers have now been able to demonstrate a pump-probe experiment, in which complex multi-photon ionization processes were studied using two attosecond pulse trains. This experiment required the generation of very intense attosecond pulses, for which a large laser system was used. Consequently, the researchers performed the experiment in the largest laboratory that is available at the Max Born Institute. At the same time, the two attosecond pulses had to be overlapped with attosecond temporal and nanometer spatial stability. This explains why these experiments are so challenging.

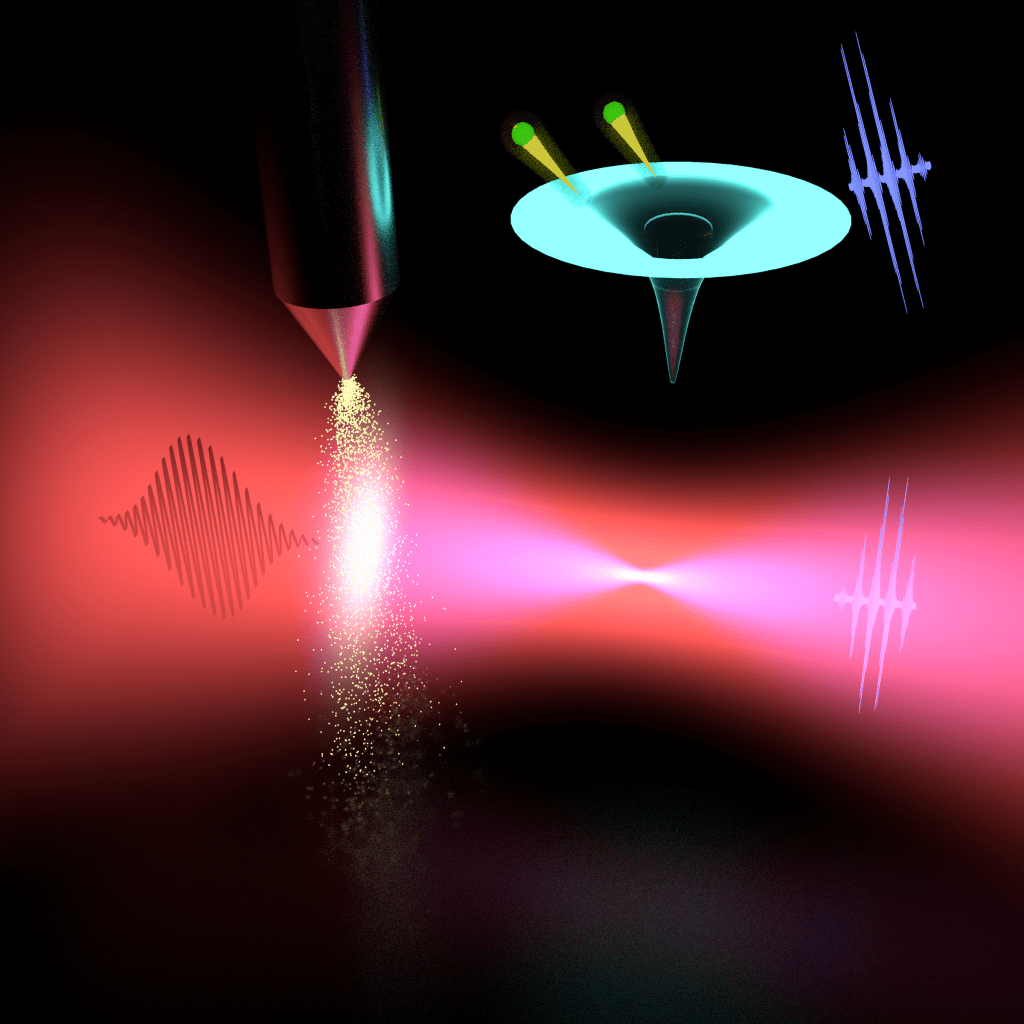

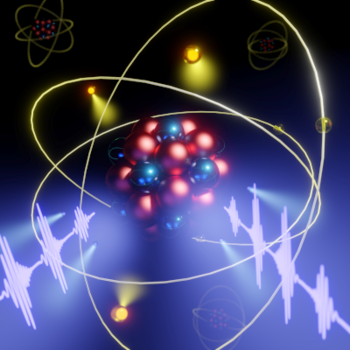

An artistic visualization of the experiment is presented in Fig. 1, showing two attosecond pulse trains interacting with an argon atom. Following the absorption of four photons from the attosecond pulses, three electrons were removed from the atom. There are many possible ways in which this multi-photon absorption may take place. To find out in detail how the electrons were removed from the atom, the researchers varied the time delay between the two attosecond pulses and observed how many ions were generated.

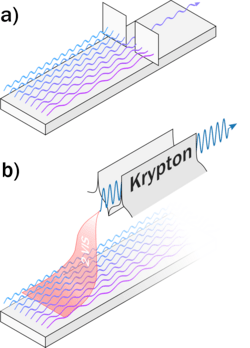

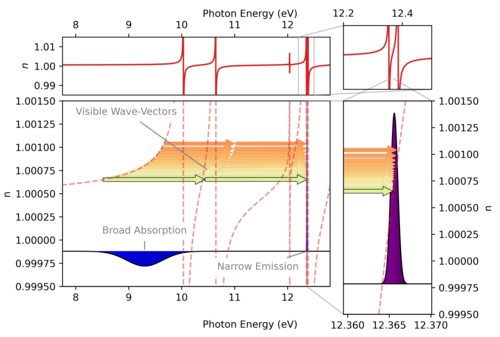

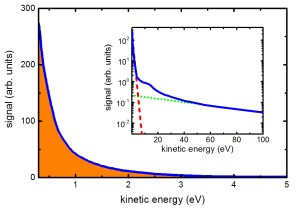

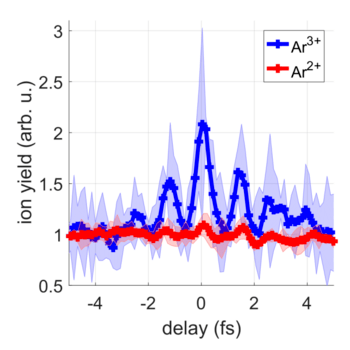

As shown in Fig. 2, the yield of the doubly-charged Ar2+ ions (red curve) was almost independent of the time delay. In contrast, the yield of the triply-charged Ar3+ ions (blue curve) shows pronounced oscillations when varying the time delay between the two attosecond pulses. The researchers were able to conclude that the multi-photon absorption occurred in three steps: In each of the first two steps a single photon was absorbed, whereas in the third step two photons were absorbed at the same time. These results were confirmed by computer simulations that were carried out at University College London and at ELI ALPS.

The developed experimental technique can be used in the future to study complex processes not only in atoms, but also in molecules, solids and nanostructures. An exciting question that the researchers hope to answer is how several electrons interact with each other. This could help to understand the most fundamental processes on the shortest timescales.

Femtosecond (1 femtosecond = 10-15 seconds) pump-probe spectroscopy has revolutionized the understanding of extremely fast processes. For instance, the dissociation of a molecule can be initiated by a femtosecond laser pump pulse, and can then be observed in real time using a time-delayed femtosecond probe pulse. The probe pulse interrogates the evolving state of the molecule at different time delays, making it possible to record a movie of the molecular dissociation. This powerful technique was awarded with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1999.

Some processes in nature, however, are even faster and take place on attosecond timescales (1 attosecond = 10-18 seconds). It would therefore be ideal to initiate an ultrafast process using an attosecond pump pulse, and to interrogate the system under investigation using an attosecond probe pulse. So far, attosecond-pump attosecond-probe spectroscopy has been demonstrated for relatively simple processes involving the absorption of two photons. However, since all-attosecond pump-probe spectroscopy is very challenging, most experiments in attosecond science use only one attosecond (pump or probe) pulse in combination with one femtosecond pulse.

The researchers have now been able to demonstrate a pump-probe experiment, in which complex multi-photon ionization processes were studied using two attosecond pulse trains. This experiment required the generation of very intense attosecond pulses, for which a large laser system was used. Consequently, the researchers performed the experiment in the largest laboratory that is available at the Max Born Institute. At the same time, the two attosecond pulses had to be overlapped with attosecond temporal and nanometer spatial stability. This explains why these experiments are so challenging.

An artistic visualization of the experiment is presented in Fig. 1, showing two attosecond pulse trains interacting with an argon atom. Following the absorption of four photons from the attosecond pulses, three electrons were removed from the atom. There are many possible ways in which this multi-photon absorption may take place. To find out in detail how the electrons were removed from the atom, the researchers varied the time delay between the two attosecond pulses and observed how many ions were generated.

As shown in Fig. 2, the yield of the doubly-charged Ar2+ ions (red curve) was almost independent of the time delay. In contrast, the yield of the triply-charged Ar3+ ions (blue curve) shows pronounced oscillations when varying the time delay between the two attosecond pulses. The researchers were able to conclude that the multi-photon absorption occurred in three steps: In each of the first two steps a single photon was absorbed, whereas in the third step two photons were absorbed at the same time. These results were confirmed by computer simulations that were carried out at University College London and at ELI ALPS.

The developed experimental technique can be used in the future to study complex processes not only in atoms, but also in molecules, solids and nanostructures. An exciting question that the researchers hope to answer is how several electrons interact with each other. This could help to understand the most fundamental processes on the shortest timescales.

Fig. 1: Two intense attosecond pulse trains (white) interact with an atom, resulting in the emission of three electrons (yellow). During this process four photons (blue) are absorbed. The probability of this process can be controlled by varying the temporal and the spatial overlap between the two attosecond pulses. Image credit: Balázs Major

Fig. 2: Ar2+ and Ar3+ ion yields as a function of the time delay between two attosecond pulse trains. (a) The Ar2+ ion yield (red curve) is only weakly modulated as a function of the XUV-XUV time delay, whereas clear oscillations with a period of 1.3 fs are observed in the delay-dependent Ar3+ ion yield (blue curve). These results indicate that Ar2+ is generated via the sequential absorption of two photons. Subsequently, two additional photons are simultaneously absorbed to form Ar3+.